Death: a passage in life

Funerals as Rites of Passage

The New Mindscape #A4–3

When someone dies, people say that they have left this world and moved to another world.

In other words, this is a passage from one state to another state.

This makes me think of the anthropological concept of “rite of passage.”[1]

The idea of “rite of passage” is that in life, we go through some important changes. These passages are not only something that we undergo as an individual; indeed, they are social passages. In each of these passages, we usually have some kind of ritual or ceremony.

Actually, the first big change that we undergo in life is when we are born: we pass out from the mother’s womb and we come into this world. That is our first big passage.

Another passage is that, in different cultures and religions, we have initiations or rites of passage in youth. For example, we have baptism and high school graduation. When you are eighteen years old, you attend high school graduation. High school graduation is often the passage from being a child to being an adult. Your social status changes from being a child to an adult. You move from playing the games of children to the role-plays of adults.

Another rite of passage is marriage: you change your status from being single to married. From this moment, you’ll start playing the role of wife or husband, in the role-play of family relations.

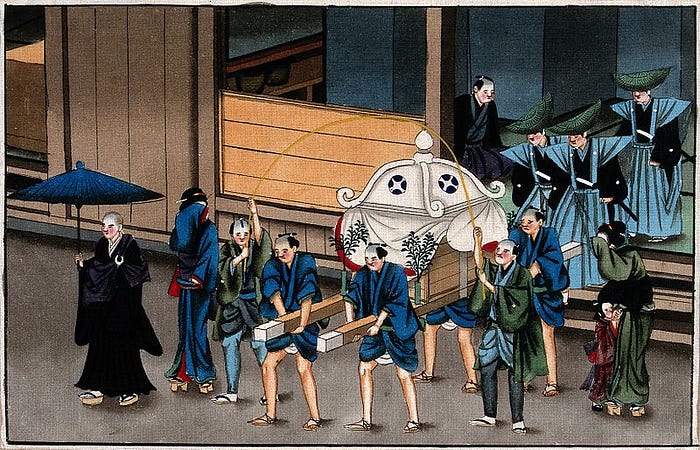

So, what is the rite of passage for the moment that we die? A funeral. The final rite of passage is death: you pass from the state of being alive to being dead, or from living in this world to living in the next world, or from being a living person to being an ancestor. We have a funeral ceremony for that passage.

The anthropologists Arnold van Gennep and Victor Turner have conceptualised rites of passage as having three stages:[2]

1. The separation stage: in this stage, the participants leave their previous state or roles;

2. The transition, or liminal stage, in which the participants are “betwixt and between”;[2] they are no longer what they used to be, but they have not yet acquired their new roles.

3. The reincorporation stage, in which the participants have acquired their new roles, or return to their normal roles.

There are also two aspects of a rite of passage. First of all, when I go through a rite of passage, I myself as an individual go through that change of roles; but secondly, the group also undergoes a change.

For example, thirty days after the birth of a baby, in some cultures, there is a naming party or ceremony. What is the point of having the naming ceremony? One reason, of course, is to celebrate the birth and the survival of the baby after 30 days. The rite of passage and the rituals often require a lot of preparation, which is supported by the participants and the members of the community.

So there’s a social dimension. People who come will support and encourage the event. And by inviting them to the ceremony, whether it’s a birth ceremony, a marriage ceremony, or a graduation or a funeral ceremony, everybody becomes aware of and accepts the fact that you have undergone a major change. They now know your new status: they now know and recognise and accept that you’re a newborn member of the family, or that you’re an adult; they now know and accept that you’re married; they now know and accept that you’re dead. As you have invited them to your marriage and they are part of this ceremony, everybody now gets used to and publicly accepts the idea that you are not single anymore and you are married, and will now be playing different roles. In the birth ceremony, they know that you are no longer parents without children and now that you have a child. Everyone will come and they accept, acknowledge, and encourage it.

This is an important point for funerals as a rite of passage. Funerals help the family and friends to collectively accept the fact that one of their own members is no longer there. There’s nobody to play that role anymore. They have to acknowledge and become aware of the fact that he or she has gone. These changes alter all the family relationships. When the baby comes in, when one of the family members get married, or when one member dies, the family relationships, the role-plays will be changed. In a rite of passage, everybody comes together, acknowledges the changes, and accepts that the relationships are changing. The rite of passage is thus a social thing.

The funeral also involves the reorganization of social relations. Let’s say the grandfather died, who was the patriarch of the family. Who is going to be the next person in authority? Who is going to play that role? The grandfather was the head and authority of the family, and after his death, the descendants have to accept the eldest son who is now the one in charge. So, the social relations will be changed.

The key point here is the importance of the social dimension of funerals as a rite of passage for both the living and dead. Every culture has this important ceremony that ensures that the dead can properly move on to the next stage. When you have a high school or college graduation, you know that now you have the responsibility of being an adult; you are no longer a child. Similarly, through the funeral, the dead know that they are no longer alive and will move on to the next stage. Funerals are important for both the dead and the living.[3]

Seeing the funeral as a rite of passage, we can also think of our life as a series of stages that we go through. Even before we were born into this world, we went through the embryonic stage, in our mother’s womb. Then we went through stages of infancy, childhood, adolescence, and different stages of adulthood. And then we move into another stage, in which our body merges with the soil, our memory and legacy continues to live among the living, and, perhaps, our spirit progresses into another world.

See the next essay, on Death in traditional Chinese culture.

See the previous essay, on Imaging spiritual reality: from death to life.

Save this URL for the whole New Mindscape series, in the proper sequence.

Join the conversation and receive updates on the latest posts in this series, by signing up for the New Mindscape newsletter.

This essay and the New Mindscape Medium series are brought to you by the University of Hong Kong’s Common Core Curriculum Course CCHU9014 Spirituality, Religion and Social Change, with the support of the Asian Religious Connections research cluster of the Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences.

[1] Arnold van Gennep, Rites of Passage. Emile Nourry, 1909; Turner, The Ritual Process.

[2] Turner, The Forest of Symbols, chap. 4.

[3] Metcalf, P., & Huntington, R. (1991). DEATH RITUALS AND LIFE VALUES: RITES OF PASSAGE RECONSIDERED. In Celebrations of Death: The Anthropology of Mortuary Ritual (pp. 108–130). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511803178.007